Introduction

Although this section started life purely as an exploration of Edwin Smith’s photography, over time it seemed appropriate to start including information on his wife Olive as well, as their lives were so inextricably linked. She now has her own section.

Contained within the site is much biographical information on both, many essays and transcriptions, together with examples of Edwin’s photographs, books, drawings, paintings and linocuts alongside biographical material on Olive, her artwork and her writings.

Acknowledgements:

I never met Edwin Smith, but his widow Olive Smith (née Cook) became a good friend of mine during the 1980s and I acted as her printer for Edwin’s photographs for many years. I created a website about Edwin after her death in 2002 as a small contribution to her life-long effort to keep his memory alive, something she had tirelessly devoted herself to since his death in 1971.

Much of the content is my personal view, based on my association with Olive and my appreciation of Edwin’s work. Where material has been gleaned from other sources acknowledgement is given. Particular thanks are due to the late Robert Elwall, for his extensive help and for giving permission to reproduce photographs from the RIBA collection free of charge. Thanks also go to John Randle of Whittington Press, for permission to reproduce many articles from Matrix and to the endlessly-patient archivists at Newnham College, Cambridge, for their cooperation on numerous occasions.

Last but by no means least, I am particularly indebted to photographer, friend and colleague, Brian Human, who has helped immeasurably during the evolution of the website. His contributions based on interviews with people that knew Edwin and Olive and his extensive research at the RIBA and of the Olive Smith Papers held by Newnham College library give the content a richness it would not otherwise have.

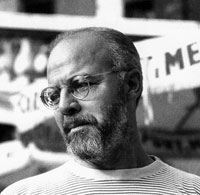

Edwin George Herbert Smith (15 May 1912 – 29 December 1971), the photographer, produced quintessential images of English architecture, landscapes, gardens and interiors.

He described himself as:

“an architect by training, a painter by inclination, and a photographer by necessity”

He considered his life to consist mainly of “going with the flow” and “co-operating with the inevitable”.

Trained as an architect, he was also a prolific artist, producing countless drawings, watercolour and oil paintings, woodcuts and linocuts throughout his life. His photographs featured in books covering a wide range of subjects and places, often produced in partnership with his wife, the artist and author Olive Cook.

His reputation as a photographer was established through the public appetite for these pictorial books, many of which became classics of their genre. This was due not only to his unique ability to capture atmospheric and definitive views of landscape and architecture with his camera, but also through the inspired and descriptive writing that Olive provided to accompany his pictures.

Through my admiration for Edwin’s photographic style and approach, I was fortunate to meet and get to know Olive in the late 1980s. We became good friends. For many years, I became Olive’s printer-of-choice for Edwin’s work, which was still much sought after for exhibition and book illustration. Although I never met Edwin, Olive assured me that I interpreted his negatives in a way that would have met with his full approval and that had he still been around we would undoubtedly have found much in common. The experience of having known Olive is one that you treasure all your life and it was with great sadness that I learned of her death in 2002.

This part of my web site is dedicated to them both as a ‘thank you’ for the friendship and encouragement Olive gave me in the years I knew her. Despite his stature within British photographic history, Edwin’s photographs were exhibited only once during his lifetime – in Cambridge in 1971, the year he died. Although there have been many exhibitions since, very little information can be found on the internet, hence these pages. He was best known through the many books published during his lifetime, and his photographs continue to be used in new publications today. Olive was a devoted widow who kept Edwin’s work alive for thirty years. Her writings were, understandably, intensely personal and appreciative. I have reproduced here the introductory essay she prepared for a touring exhibition called ‘Record & Revelation‘ organized by Impressions Gallery, York, in 1983. An independent assessment of Smith’s work was long overdue and the publication of Robert Elwall’s excellent book, ‘Evocations of Place‘ provides a fresh assessment of his place in photographic history.

The reproduction quality of the photographs in this book, printed in Italy, is high, although not perhaps to the exacting standards of photogravure that Smith always insisted upon. The design of the book is admirable though and would, I think, have met with Olive’s approval. A review of it is included on this site.

In 1993 , Olive gave me one of Edwin’s cameras, first as a loan and then as a gift. Unbeknown to her, this Ensign Autorange 820 still had in it the last roll of film that Edwin exposed in 1970. I developed and printed this 23-year old film and Olive recalled – as she did with every one of Edwin’s photographs – the time and place the pictures were made. These are most likely the very last photographs that Edwin ever made, certainly the last that he exposed in the Autorange. He never saw these pictures developed and printed. You can see them here.

In working with Edwin’s negatives, I soon realised that the prints he originally made relied on a fair degree of manipulation to get the tone and the mood just so. Some of them I found almost impossible to reproduce exactly using modern photographic print emulsions. Many hours were spent in the darkroom experimenting with different papers and processing techniques in order to try and match the original print by Edwin that I had as a guide.

When presented with one of my prints of Edwin’s work that I knew wasn’t perfect but was the best I was able to achieve, Olive would often say “You haven’t quite got it yet dear, have you?” I knew that meant that it didn’t meet her exacting standards and that I’d be back in the darkroom again. Although Edwin was a gifted printer, I sometimes felt that some of the prints he left were not those that he would consider ‘finished’. Nevertheless, in Olive’s eyes they were the definitive interpretation of his intent and few of my ‘improvements’ would ever gain her full approval. I resigned myself to this, following Edwin’s maxim of ‘co-operating with the inevitable‘. I learned more about printing in the years I worked on Edwin’s negatives than at any other time in my career.

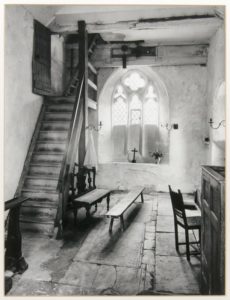

This passage by Olive, describing the location of some of Edwin’s photographs, typifies her writing style. It is as evocative to read as the resulting pictures are to view:

“The light was marvelously expressive, a dream-like twilight which revealed every tile and plant and enhanced the strange reality of an incredibly romantic crucked and crooked manor house juxtaposed to prim Georgian cottages and shallow gardens enclosed by fat, closely cut hedges or white railings. This chance of light, moment and mood produced some magical photographs.”

The picture of Didmarton Church reproduced on the left is not the one described, but it conveys the same magical feeling for light, content and composition that is apparent in so many of Edwin’s pictures. I have a print of this hanging in my house and never tire of looking at it. There is also a copy in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Edwin left us at the peak of his flourishing career, and he is justifiably counted amongst those British photographers who helped establish a characteristic ‘English’ style of topographic imagery that was further refined and explored – albeit to a different agenda – by Raymond Moore and Fay Godwin. Although the subjects of his photographs were often archetypes of our architectural and rural heritage, his approach to them went beyond mere documentation. The title of his show at Impressions Gallery, Record and Revelation, is particularly apt, as is the title of Elwall’s book. He brought an exploring artist’s eye to photographic representations of our architecture, culture and environment, revealing more than just the subject in a way that was quite unique.

Olive once said of Edwin, whom she often called ‘E’, or more frequently ‘my darling’ :

“E always lived absolutely in the present, and used it to the utmost; one of the delights of living with him was to feel his intense awareness of the divine, magical, ecstatic reality of the moment.”

At one point Olive and I discussed where Edwin’s work should end up when she died and she decided that the entire collection would be bequeathed to the National Media Museum in Bradford. She obviously had second thoughts about this over the years and, following her death, the archive was left to The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) where it resides today and to whom copyright on all his photographs now belongs. This was an excellent choice, given that Edwin was himself an architect by training and that many of his photographs celebrated the beauty of the constructed form, in all its many variants. Around 60,000 photographic negatives by Edwin Smith are now being catalogued and professionally conserved. Online versions of many of his pictures are also being included in the searchable RIBA image database, Currently (Nov 2006) over 700 photographs by Edwin have been made available to view – and purchase – via RIBApix.

The Fry Art Gallery, in Saffron Walden, Essex, and The Minories Gallery, Colchester, also hold examples of work by both Olive and Edwin, as does Chelmsford Museum in Essex.

© Roy Hammans, 2007 (Updated 2017)